PRODUCTS ARE AT THE HEART OF A SUSTAINABLE BUSINESS STRATEGY

SUSTAINABILITY HAS ARRIVED IN THE CORE BUSINESS

In the past, corporate sustainability was often viewed as something additional, sometimes even as a cost-intensive accessory: in addition to the “actual” corporate strategy, there was also the intention to do something good. Sustainability had nothing to do with the business model, i.e., how the company earns money, except as a cost factor and thus a candidate for budget cuts. As a result, sustainability gained a place on the board agenda primarily through risk management – for example, raw material shortages and reputational damage.

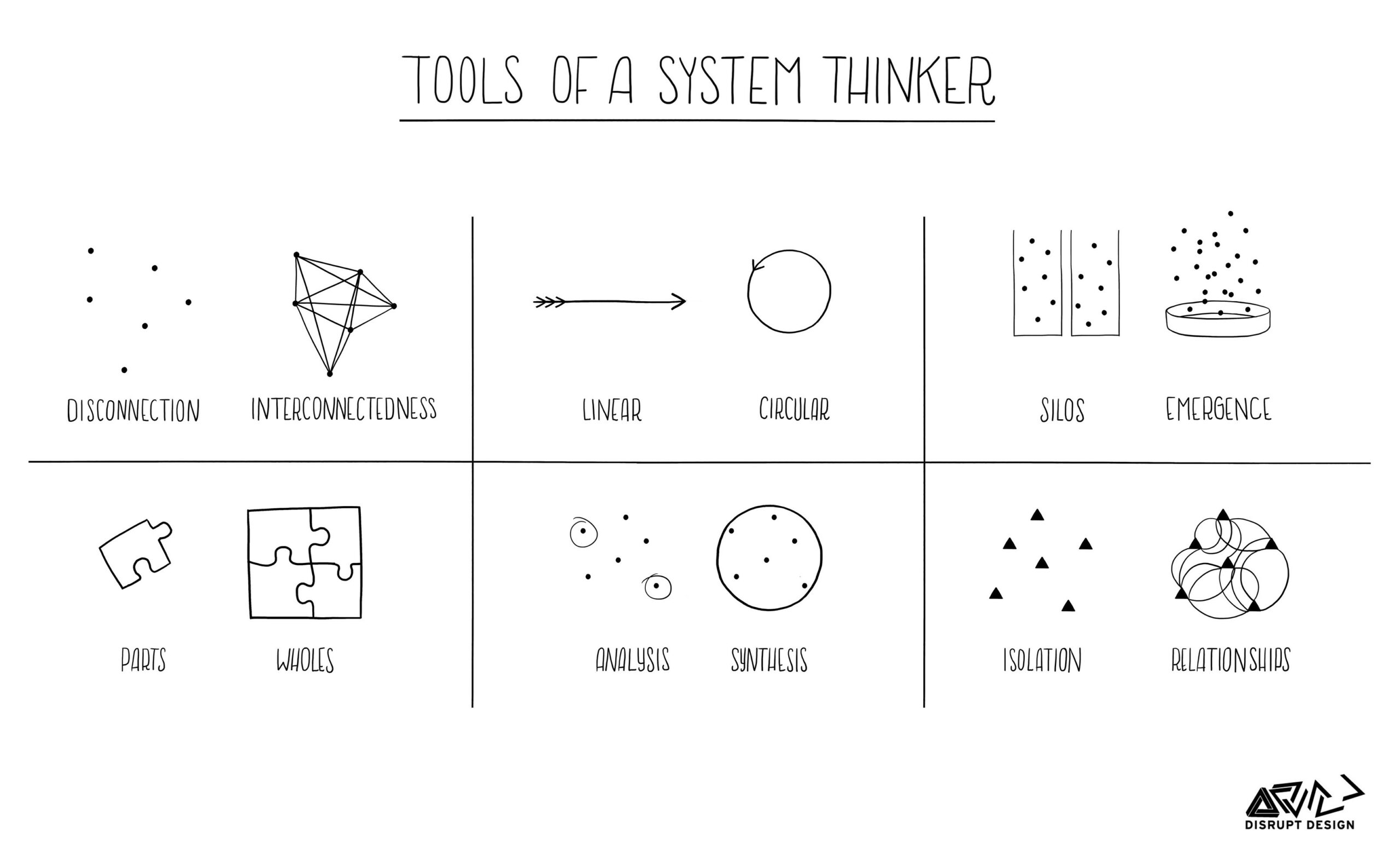

Since then, not least under the impact of the climate crisis, the realization has matured that a very fundamental transformation of economic activity is indeed necessary. The classic, linear, energy- and resource-intensive economic model has led us into this climate crisis. Now that boardrooms are considering circular and net-positive business models, sustainability has arrived at the heart of core business. “The product reflects the sustainable corporate strategy” – what does that mean?

CONFLICT WITH GROWTH ORIENTATION

This is easy to see in a common product such as the smartphone. If the energy consumption of all smartphones can be reduced by ten percent, the leverage effect of large quantities will result in significant savings. This economies of scale effect is essential for overcoming the energy and raw materials crisis. At the same time, however, the example of the smartphone also makes it clear that the utility value of communication, entertainment, and other functions is so attractive that in a growing market with short product cycles, reducing energy consumption is far from sufficient: the savings are more than offset by market growth and intensity of use (rebound effect). This means that strong demand for innovative products negates their sustainability effect, as the high volumes result in even more energy being consumed overall.

PRODUCTS MANIFEST THE ECONOMIC SYSTEM

The product is therefore the key to transforming the economic system. The company is expanding its business model to explicitly include a contribution to social issues. This can be done by meeting basic needs, for example with a medical device that enables people to participate in society. It can also be done by respecting planetary boundaries, for example by achieving a scalable supply of renewable energy. The term “benefit” encompasses both technical-functional and aesthetic-emotional components and is reflected in customers’ willingness to pay. Starting points for greater sustainability can therefore be found in both product benefits and the resources used to achieve them.

More benefit with fewer resources

is a good, albeit insufficient, formula. This is because efficiency alone does not usually prevent the rebound effect.

How can we decouple utility value and resource consumption?

Can the contradiction with growth orientation be resolved at all?

FROM PURPOSE TO STRATEGY

To do this, we need to reflect on the corporate purpose: Why does the company exist? How does it create a better world? In order to develop a sustainable corporate strategy, we must therefore answer the question of how, despite and precisely because of commercial scaling, human needs can be met within planetary boundaries. The core of such a sustainable corporate strategy is therefore the long-term product strategy: it describes how the company fulfills its purpose by creating social benefits and sustainable solutions. For example, the corporate purpose of a packaging manufacturer could relate to the protection and shelf life of valuable, vitamin-rich foods.

Until now, this has been ensured by a disposable system with correspondingly high material costs. However, the solution space is not linked to a specific product or material solution from the outset.

For example, a recyclable (circular) product such as high-quality reusable packaging can fulfill its purpose again and again without the use of new raw materials.

Because products can shape and change consumption patterns, they have disruptive potential: the next stage of development could be the replacement of lemonade in disposable bottles with microdrinks made from extracts in reusable containers.

PRODUCTS CONVEY A MESSAGE OF SUSTAINABILITY

In addition, thanks to improved transparency in general and disclosure requirements for product information in particular, much more is known about the story behind the product. The product itself becomes a message. It conveys how corporate sustainability and product responsibility are put into practice. The product reflects the sustainable corporate strategy. For example, the food industry is undergoing a shift toward extensive traceability, so that the product’s journey from cultivation to consumption can be traced. The concept of a digital product passport (DPP) suggests that such developments can also be expected in other sectors.

INNOVATION MANAGEMENT NEEDS SUSTAINABLE GUIDELINES

IDEALITY MEANS MAXIMUM BENEFIT WITH MINIMUM EFFORT

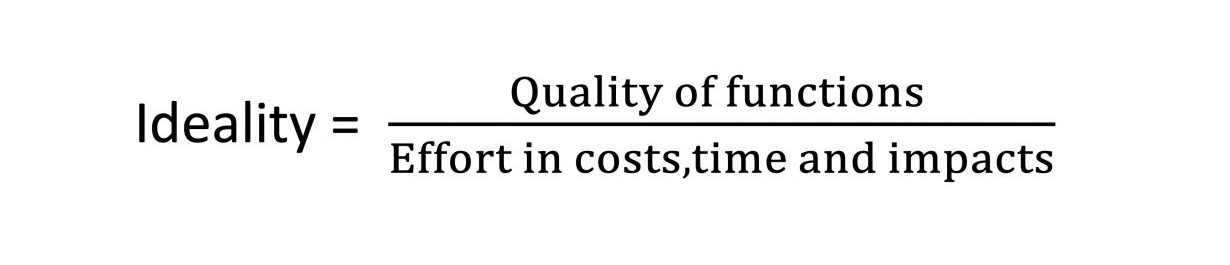

The product benefits, i.e., function and quality, determine its value in the eyes of the customer. In an ideal world, unlimited benefits could be achieved with negligible effort. That is why innovation research refers to the relationship between benefits and effort as ideality.

- Research and development will primarily focus on increasing the benefits of the product. One example is energy or data storage devices with ever-increasing capacity. In addition, positive external effects can be achieved by the product itself or along its value chain. Think of building products such as windows and facades, which contribute to energy efficiency and safety, the appearance of the neighborhood, and the quality of life for the general public.

- At the same time, it is important to reduce costs and time expenditure. When developing sustainable products, we also take responsibility for initially hidden risks and side effects, for example in the supply chain or in the ecosystem. By internalizing negative externalities, another cost factor is added: environmental impact.

Impact is measured by indicators such as the ecological footprint. The carbon footprint (product carbon footprint) is a good leading indicator because it reflects both energy and, to some extent, raw material intensity. The ecological footprint also takes other environmental impacts into account: for example, it shows that lithium-ion batteries are a highly raw material-intensive technology and that mining them has further ecological consequences in terms of water consumption, salt pollution, and landscape degradation. At the same time, recycling after use offers the opportunity to close the lithium recycling loop, especially for a country like Germany, which is poor in raw materials. And because of the logistics involved, this is naturally more feasible with a leasing system, which in turn suggests a change in the business model.

ECOLOGICAL BALANCE SHEET AS A COMPASS FOR INNOVATION

The actual purpose of an ecological balance sheet (life cycle assessment), which covers other environmental impacts in addition to the carbon footprint, should therefore be to provide key figures to support strategic planning and targeted innovation, rather than being limited to market-oriented communication. Rather, the life cycle assessment identifies starting points for the continuous improvement of the product carbon footprint, whether it is more about energy consumption in the use phase or the use of circular materials in manufacturing – and how these two areas influence each other. It is important not to lose sight of the connection with the function and benefits of the product. On the path to innovation toward ideality, benefits can be increased and costs reduced.

CONNECTION WITH SCOPE 3

At the same time, this opens up opportunities for effective climate strategies in the otherwise difficult Scope 3 of the company, i.e., the contribution of purchased materials and goods to the carbon footprint of the entire company. We can therefore establish a connection: If the life cycle assessment reveals significant starting points for materials and intermediate products, the analysis of Scope 3 (upstream) can be used to identify the 20 percent of purchased goods that account for 80 percent of the corporate carbon footprint. If this is not the case, the reduction potential is more likely to be found in the downstream of Scope 3 or in the so-called Scope 4: Product development should focus on corresponding improvements in usage properties or end-of-life management.

For example, thinking about products with as little packaging as possible – often combined with omitting water from the recipe – has often led to radical innovations in the food sector as well as in cosmetics and household products that use significantly less material. Such considerations often lead to innovations and, as a result, to a new and perhaps even disruptive business model. This requires the integration of sustainability principles into both innovation management and product management. So, to develop a sustainable corporate strategy, include both product benefits and resource consumption in your considerations.

Author

Dr. Ing. Ivo Mersiowsky is a consultant and coach for sustainability in product management and corporate governance. As an environmental engineer with a specialization in innovation coaching, he has been active in sustainability management for over 25 years, with experience in the chemical industry, a testing company, and various international consulting firms.