Sustainability issues such as climate change, deforestation, water scarcity and biodiversity loss are becoming increasingly relevant in the public sphere and political discourses. However, few solutions have been proposed and translated into effective action. Wicked problems are complex and extremely hard to solve because of incomplete, contradictory and changing requirements. They usually (1) involve multiples stakeholders whose values are different, sometimes even opposite, (2) lack definite formulation of the causes and (3) have solutions that are not right or wrong but can be better or worse.

Sustainability issues are wicked problems. Firstly because all proposed solutions remain limited and temporary compared to the complexity and depth of the sustainability problem itself. Secondly, because this complexity increases even further when we take into consideration stakeholders involved and their conflicting values. Lastly, they are issues that require a long-term approach that go beyond our lifetime and future generations.

The endeavor of solving sustainability problems is a challenge that needs to be addressed at every level of society (DESA, 2013). The task seems even more daring given that at the core of sustainability issues lie complex and dynamic challenges that our traditional lineal system fails to tackle (Osorio et al., 2009), hence forcing communities to find new models and paradigms to solve them (Sala et al., 2015). Latest research reveals the fundamental complexity of ecosystems and the inability of ecosystem management to predict the cascade effect of actions that take place across the system (Defries et al., 2017). The biggest impediment for tackling sustainability problems is the lack of (1) collective action and (2) a long-term scale, needed to address such complexity.

If any individual decides to shift to a more sustainable life, where should she or he start? They might already own the most important element: the intention. But, how to translate that intention into effective action, that is the golden question.

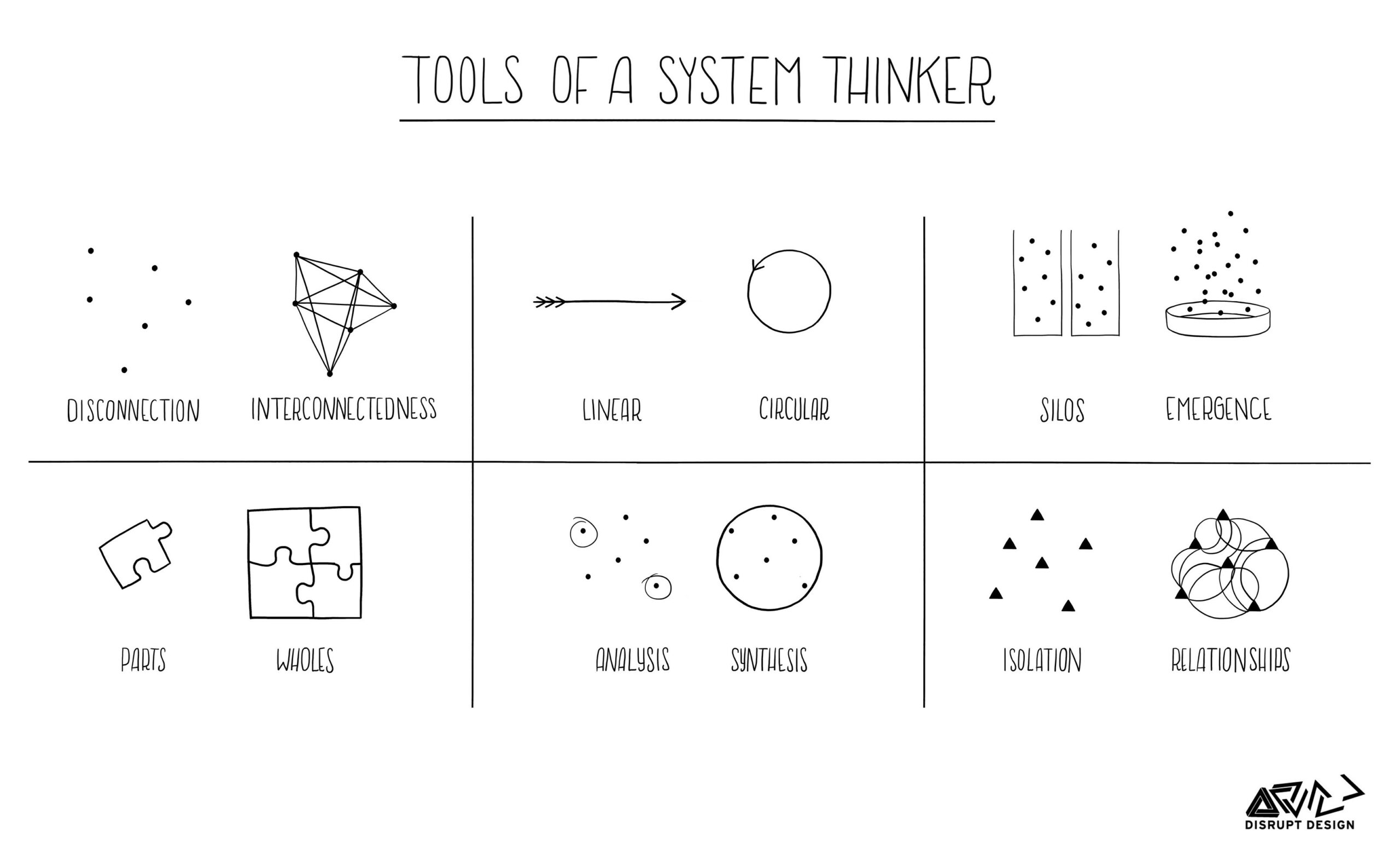

There are several existing frameworks that dive into the complexity of sustainability issues to expand the awareness on how our collective day-to-day decisions accelerate the on-going depletion of our vital resources. Being sustainable is not about doing A instead of B because B is bad and A is good, as a matter of belief. It is rather about shifting the source of our actions, so that our decisions become the result of our understanding of the collective and complex nature of our current systems.

Having a better grasp of the interconnectivity of things can help us make better choices than becoming blind followers of an orthodox way of living, even questioning our own longstanding values. This open attitude and critical thinking will also help reach the indecisive population that are skeptic about change and who are turned off by the shame installed by extreme positions. This type of shaming feeds the sense of hopelessness that activates the cynical voice saying, “The world is doomed anyway, and there’s nothing I can do to change it”. There’s a call for new storytelling: new frameworks that will allow us to expand our understanding of the dynamics and impacts behind our decision-making. I will now introduce three interesting frameworks that offer a holistic approach to sustainability issues and complexity: the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) (Kristensen, 2004), Resilience Thinking (Stockholm Resilience, 2019) and Transition Design (Irwin, 2018).

DPSIR

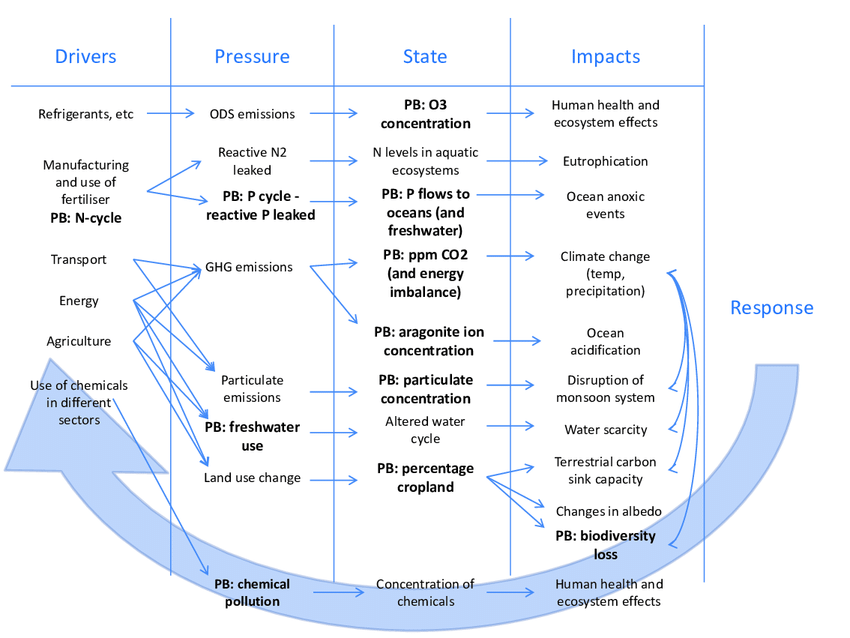

DPSIR approach is based on the idea of chain of causal links starting with driving forces (ex: economic sectors, human activities) that through pressures (ex: emissions, waste) affect different states (physical, chemical and biological) and generate impacts (ex: ecosystem, human health and functions), eventually leading to political responses (ex: prioritisation, target setting, indicators) (Kristensen, 2004) (See figure below). DPSIR can be applied to all types of sustainability issues. However, establishing a DPSIR framework for a particular setting is a complex task as all the various cause-effect relationships have to be carefully described and environmental changes can rarely be attributed to a single cause. It is very useful to show the natural phenomena and the interconnections in a desegregated way.

Example of National Environmental Performance on Planetary Boundaries in a DPSIR framework

Source: National Environmental Performance on Planetary Boundaries January 2013 Publisher: The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency ISBN: 978-91-620-6576-8 Björn NykvistBjörn Nykvist

Resilience Thinking

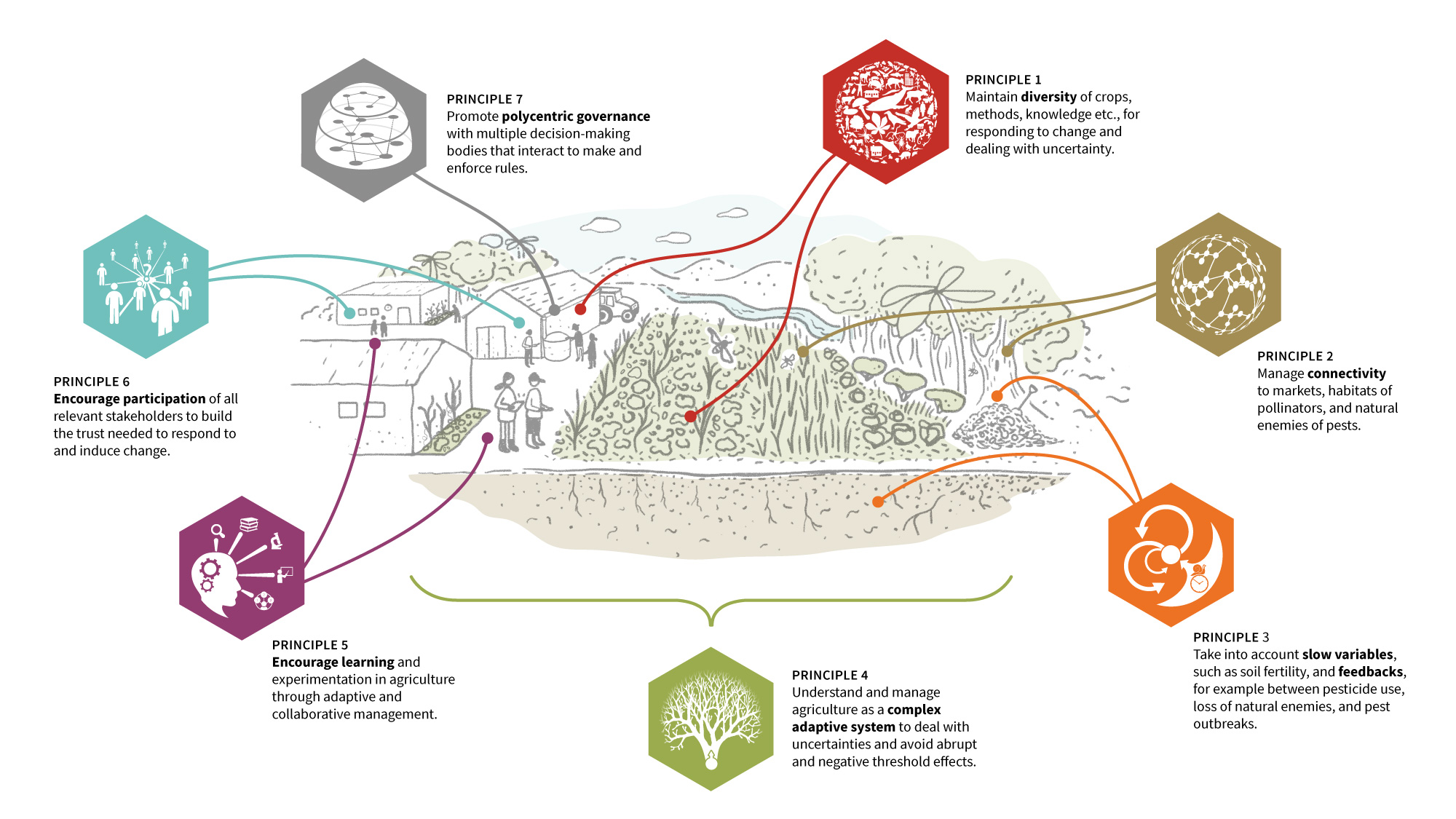

Resilience thinking, on the other hand, studies how integrated and complex combination of both ecosystems and social systems cope with uncertainty (Berkes & Folke 1998, Anderies et al. 2004, Walker et al. 2004). It assumes resources humans use are embedded in complex, social-ecological systems (SESs) composed of multiple subsystems and internal variables within these subsystems at multiple levels (Ostrom, 2009). Many resilience researchers are interested in how to avoid collapse and actively transform systems to new better states. They focus on how these interacting systems of people and nature can best be managed in the face of uncertainties. According to them, resilience is the capacity of a system, be it an individual, a forest, a city or an economy, to deal with change and continue to develop. It is different from other frameworks given its subjective rather than objective view of systems. Founded in systems theory, it aims to articulate the subjective perspective from which a system is analysed to assist in the mapping and translating between multiple perspectives. Resilience thinking is based on 7 principles. The first (1) principle is to keep as much diversity and redundancy as possible since experience has shown that the more diverse the components (species, knowledge, stakeholders) the more resilient they become. The second (2) principle is to manage connectivity. According to them connectivity is two fold: well-connected systems can have faster recovery but over-connected systems may lead to an uncontrollable chain of disturbances. The third (3) principle is to keep slow variables and feedbacks (both positive and negative) under control in order to assure ecosystems essential services. The fourth (4) principle is to encourage complex adaptive systems thinking. This is to accept that within a social-ecological system, several connections occur simultaneously and at multiple levels. It implies the acceptance of uncertainty and acknowledgment of the multiple perspectives available on the same issue. The fifth (5) principle is to encourage continuous learning. According to resilient researchers, socio-ecological systems are under constant change and this demands an ongoing reconsideration of existing knowledge to promote new learning and increase collaboration with more stakeholders and new ideas. The sixth (6) principle is to broaden the participation needed to activate collective action. Awareness and dynamic horizontal organisations have the potential to build trust and share the knowledge crucial to promote collective action. Last but no least, the seventh (7) principle is to promote polycentric governance. This implies a multi-level governance system in which multiple governing bodies interact to make and enforce rules within a specific policy location in a more flexible way. These flexible solutions for self-organizations are more effective than slow formal procedures that often fail. That being said, these principles implementation remain a challenge to our societies. They also imply trade-off negotiations between diverse users of ecosystem services, which could make it harder to put into practice.

Ex: André Gonçalves’ research has looked at how the seven resilience principles manifest in practice in agroecological farming. Illustration: E. Wikander/Azote

Transition Design

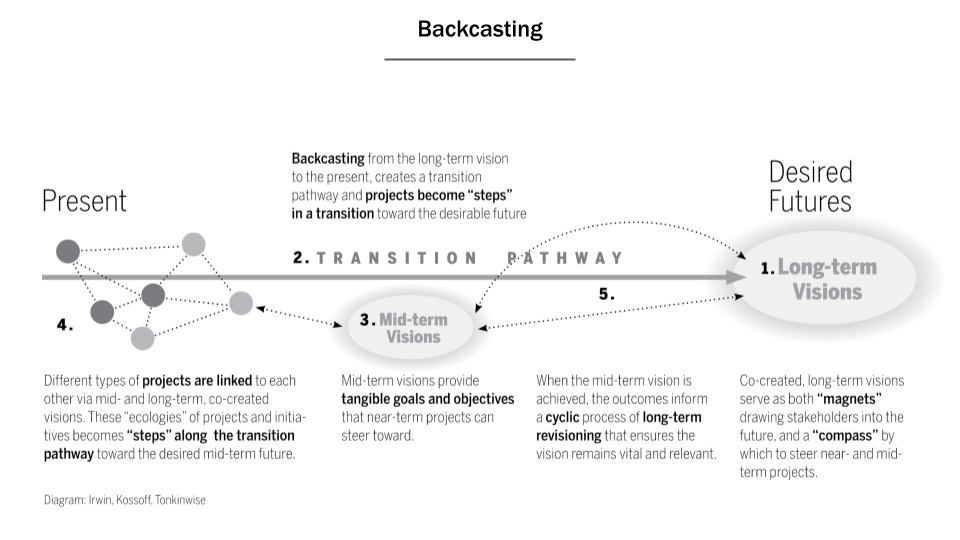

Lastly, transition design defines three types of systems; living system, the socio-technical systems and wicked problems, this last one understood as system problems (Irwin, 2018). Transition designers’ main concern is how to plant and catalyse system-level change knowing that it might take decades to understand the systems and its dynamics. All three systems exist at multiple levels of scale, are interconnected and interdependent and their dynamics are defined by feedback loops, which explain the ‘butterfly effect’: the unexpected fast ramifications throughout the system produced by the most insignificant event. Transition design is characterised for stressing (1) the importance of stakeholder participation in mapping wicked problems in order to build consensus and effective change, (2) developing long-term future scenarios in order to trace the paths of change and (3) thinking in terms of ‘systems interventions’ instead of one-off solutions. Transition designers believe that changes in lifestyle are the fundamental context to implement solutions and that systems-level change is per se trans-disciplinary. They suggest that “system-level” change should be applied in three phases: re-framing the present and future; designing interventions and waiting and observing (see figure below). The basic idea is to execute the projects returned from the future, monitoring the results and correcting the vision continuously in a process they call “backcasting”.

To conclude, all of these holistic frameworks provide a good foundation to expand our understanding of the dynamics behind our decision-making and conceptualise how sustainability can be brought upon in a given system. However, the key question remains unanswered: how to accelerate the transition to more sustainable decision-making processes? Classical decision-making paradigms have proven their limits in curbing problems such as climate change, food shortage and deforestation. There is an emerging need for new collective decision-making mechanisms to allow diverse stakeholders to connect, re-think and bring forward solutions for sustainability issues.