THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY HAS ENORMOUS POTENTIAL FOR INNOVATION. COMPANIES CAN BECOME MORE RESILIENT, DEVELOP NEW BUSINESS MODELS, DIFFERENTIATE THEMSELVES FROM COMPETITORS AND ACHIEVE A BETTER ENVIRONMENTAL FOOTPRINT. AT THE SAME TIME, THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY IS NOT NEW. LET’S TAKE A LOOK AT THE TEN STRATEGIC APPROACHES FOR MORE CIRCULARITY.

First extract raw materials from the earth, make a product from them and see how you can sell it – the customer will surely dispose of it properly – that sums up the linear economic model. Raw materials are not returned to the cycle. There is no systematic approach to reuse or recycling. The question remains: Can we afford it? Beyond pollution, footprint and planetary boundaries, what about raw material availability, purchase prices and resilience? What do we do when the availability of raw materials is no longer guaranteed? Isn’t it wiser in the long run to choose a business strategy that doesn’t follow the principle of higher, faster, further? What will our business models look like in five, ten or fifteen years? What are ten strategic approaches for more circularity in business?

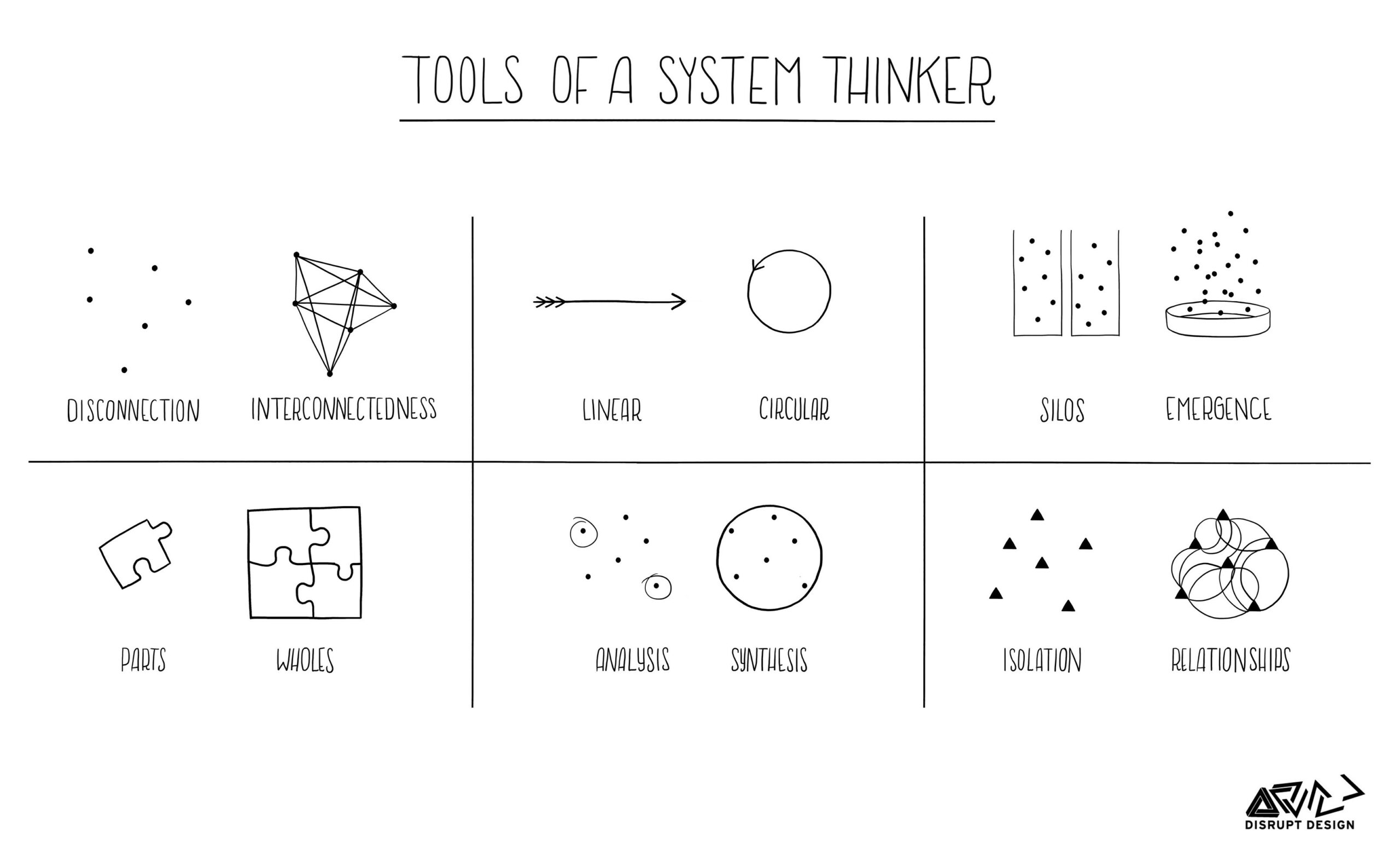

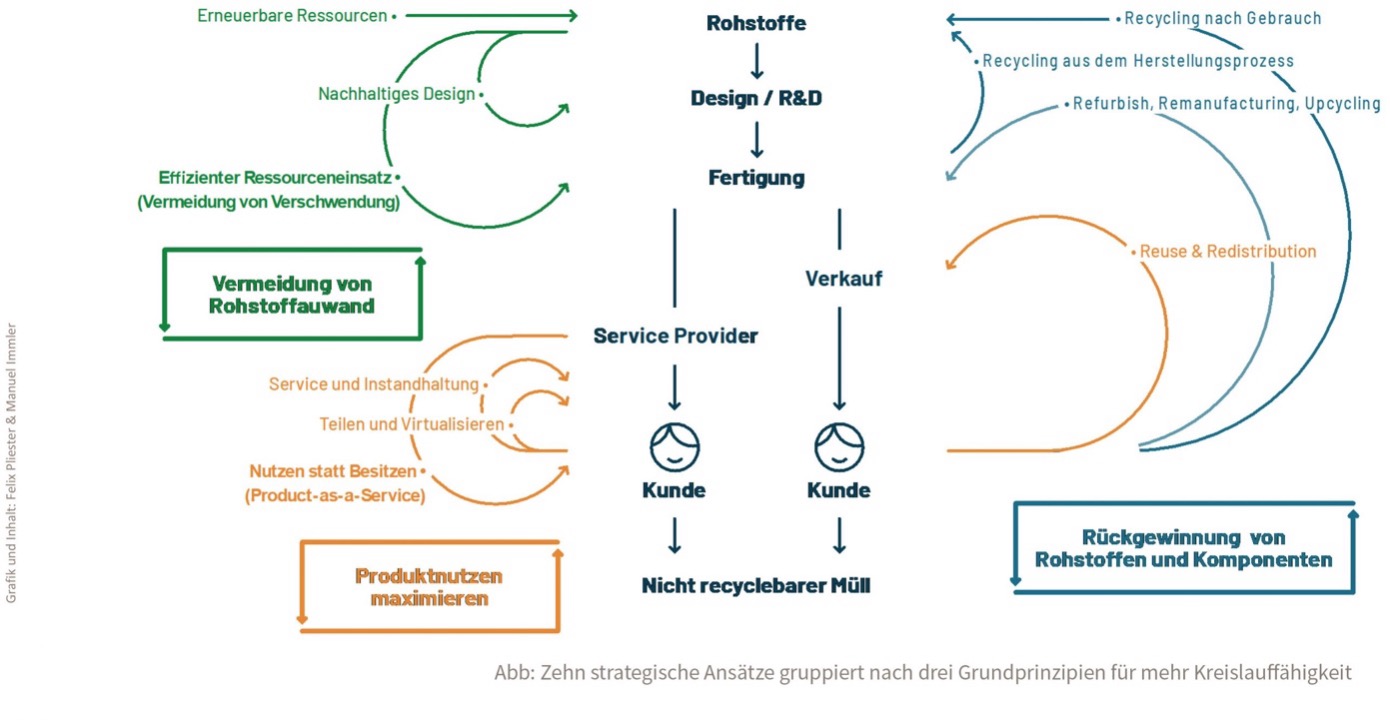

The circular economy itself is nothing new. Historically, people have always thought in terms of cycles. The moment it became cheaper to extract raw materials than to reuse them, the pendulum swung the other way. It is only in recent years that the sense that raw materials are unlimited and always available has begun to crumble – apart from temporary shocks such as the oil crisis. The pandemic showed what happens when global supply chains suddenly stop working. What remains are trade flows that are fundamentally reorganised . For this reason alone, it is worth questioning one’s own circularity in order to keep raw materials in the system as well and as long as possible. Basically, there are three principles that can be pursued in one’s own strategy:

1.Recovery of Raw Materials

2.Avoidance of Raw Material Use

3.Maximizing Product Utility

HOW DO THESE THREE PRINCIPLES WORK IN DETAIL?

When we think of the circular economy, the first thing that probably comes to mind is the recovery of raw materials. Everything that is created during production or at the end of a product’s life is collected and recycled. According to a study by the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, per capita consumption of raw materials in Germany is 17 tonnes (2018). On average, only 12% of this material is recycled. For metals, which are easy to recycle, the rate is slightly higher at 33%. The potential is not yet fully exploited: instead of 16%, up to 47% of gold from electronic devices could be recycled; for silver, a recycling rate of over 54% is theoretically possible – today it is 16% – and researchers are currently testing methods to recycle more than 90% of lithium-ion batteries.

The difference between recycling and upcycling, refurbishing or remanufacturing is that in recycling the product itself is broken down into its raw materials before being reused. In contrast, remanufacturing involves refurbishing parts of the product (components) or the entire product itself and returning it to the market as a new product of equal or higher value.

To give a few examples from the B2B sector:

- Caterpillar, the US manufacturer of construction equipment, turbines and engines, has a comprehensive remanufacturing programme for its products called “Cat Reman“ . It is not uncommon for an engine to be completely overhauled and given a second life in another construction machine.

- Siemens does something similar with medical equipment, such as CT or MRI scanners, as part of its “Siemens ecoline ” programme. Furniture is often too valuable to be disposed of at the end of its life. The Swiss company Girsberger, for example, refurbishes seating for concert halls.

Reconditioning is also exciting when it comes to household appliances (by Norsk Ombruk in Norway) or supermarket refrigerators (by the Bond Group in the UK), which often return to the market with improved performance.

Finally, we should mention the packaging produced entirely from agricultural waste by Bio-Lution.

The second principle on the way to a more circular economy is to reduce the use of raw materials. What has been done everywhere, especially in recent decades, is to increase efficiency. This means removing waste from processes, usually under terms such as lean management or lean production. More interesting, however, is the question of whether the raw materials used can be replaced by renewable options; several car manufacturers, for example, are working on the use of alternative materials. However, the key to this strategic approach lies in the design itself. Intelligent design can dramatically increase the lifespan and recyclability of products. While the approach depends on the product and business model, there are six basic design principles that can be used as a guide:

- Manufacturers can design their products and communications to create a strong emotional bond and keep customers loyal for as long as possible. A timeless design that is not subject to fashion trends, for example, is one way forward.

- Physical durability plays an important role in ensuring that the product can be used for a long time. This depends on the materials used and the quality of manufacturing.

- When standards are used, products can be used more easily with other products. It is also easier to achieve better repairability.

- Repair and maintenance are also key to extending the life of a product. Design can already facilitate repair and maintenance in a number of ways.

- In addition, the design should allow for products to be adapted to new circumstances or even improved through “upgrades”.

- Finally, a product should be designed to be easily disassembled for recycling.

Increasing product utility is the third principle on the path to a more circular economy – and probably the one with the greatest potential for innovation. To meet customer needs holistically, the product is embedded in a service offering. The customer benefits by receiving a complete solution rather than just a product. It also means that the manufacturer becomes a service provider. In its simplest form, a service and maintenance logic is established. The product is accompanied by a promise, such as greater reliability or an extended range of services.

Depending on the product, a “use instead of own” logic is also conceivable. The customer uses the product only as long as he needs it. In the meantime, the same product is used by other customers. Utilisationincreases and the product is usually offered at a higher margin. However, this also means that products have to be designed with completely different requirements than today. Suddenly it becomes even more interesting for the supplier to increase maintenance and repair options and also to extend the life of the product. If a product that does not break down is currently a disadvantage for the manufacturer – because the customer does not come back for a second purchase – it will now be worthwhile to design products that do not wear out.

At the highest level, products are shared. The product is not permanently owned by one person, but goes through several cycles. The business model here is a kind of intermediary that brings customers and products together via a virtual platform.

Several such business models already exist today:

- The classic example is car sharing. Instead of buying a car, the customer buys mobility.

- Linde is no longer just selling forklifts. In essence, it sells peak coverage in intralogistics.

- ELVIS is a partial load system for freight forwarders. Instead of a truck, a transport volume is sold that can be called up as required.

It is time to bring the old approach of the circular economy into the present. Companies and societies are looking for radical changes in the way our business models are structured. Of course, legislators can create incentives to pave the way for more circularity. In this article, we have also outlined ten strategic approaches to greater circularity that every company can take direct action on. What is clear is that today’s linear economic model is unsustainable and needs to change. And sooner rather than later, because the problems it causes are becoming more urgent. Businesses need to act now and take new paths towards greater circularity.