Content

- What COP30 actually decided

- Why Belém was the right place

- Where business is heading

- Corporate strategies

- Accountability and governance

- The perspective of finance

- Public policy and new leadership

- Conclusion: a clear global direction

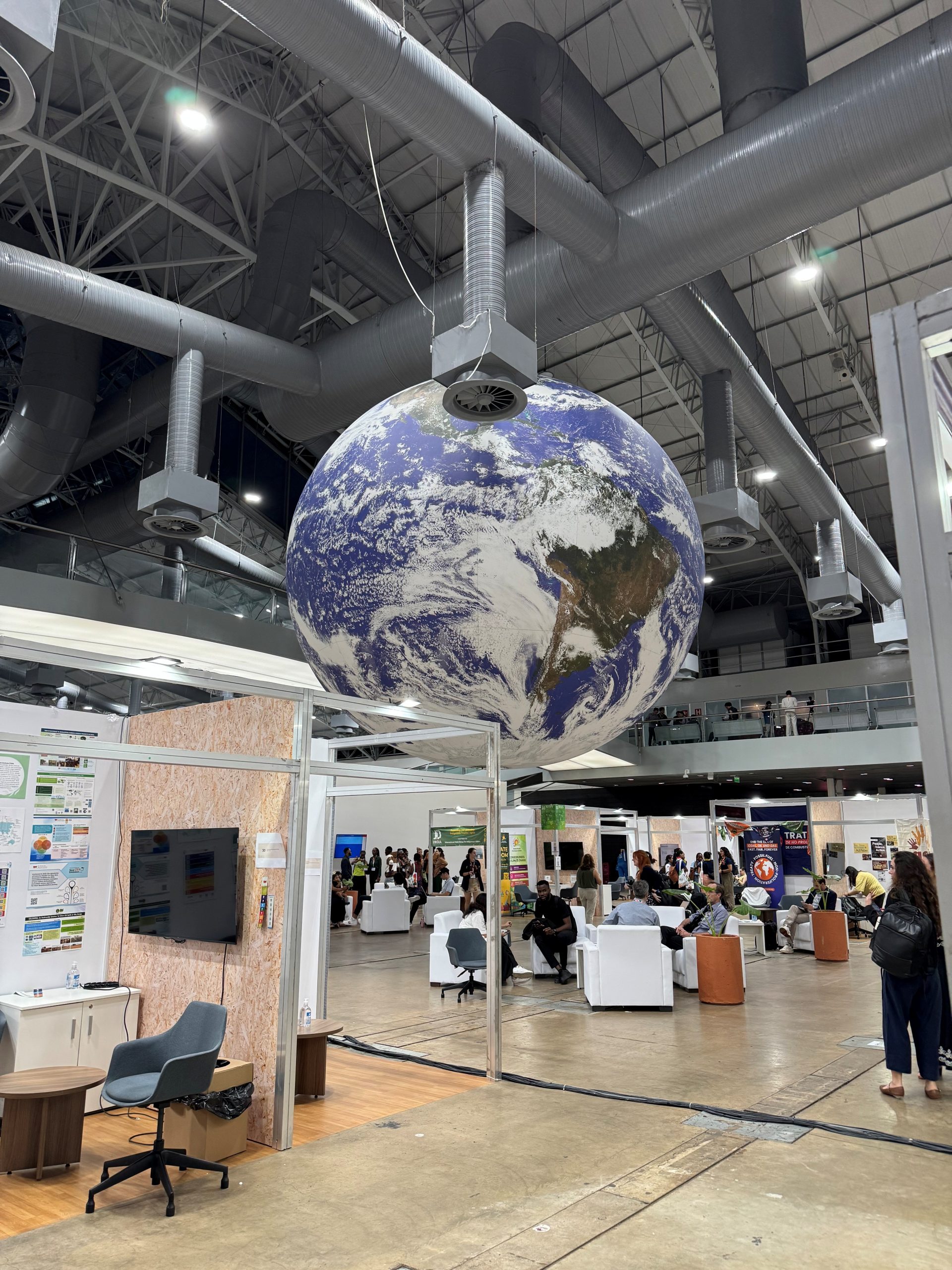

“When we think of a climate summit, Belém do Pará is hardly the first place that comes to mind: a port city on the edge of the Amazon, marked by chaotic traffic, stark inequality and tropical humidity. And yet it was precisely there that, as an observer together with an association from Trento, I took part in COP30.” – Annika Zamboni

Belém is a city of contrasts, made even more visible during the event: large air-conditioned pavilions next to fragile neighbourhoods, a mega international gathering in a setting of precarious infrastructure, debates on a “just transition” in a country that still partly depends on fossil fuels. Perhaps this is exactly the point of holding a COP in the Amazon: here you really see the world, with all its fractures: Global North and Global South, financial centres and Indigenous communities, multinationals and social movements forced into the same space for two weeks.

Beyond negative headlines: what COP30 actually decided

In the days following the close of COP30, much of the media has focused on an almost exclusively negative reading of the outcome: “no deal on fossil fuels”, “failure on coal phase-out”, “Amazon betrayed”. This narrative has real foundations, but in my view it reflects only part of what was actually decided in the negotiating halls.

The Mutirão Decision, the final political text adopted in Belém, does not explicitly mention fossil fuels and does not fully embrace President Lula’s call, supported by more than 80 countries, for a global roadmap on fossil fuels and deforestation. From this standpoint, disappointment is understandable.

At the same time, the overall package includes important steps forward, especially on international cooperation and climate finance. Within this framework sits the so-called Belém Package, the set of technical and financial decisions that give substance to the Mutirão Decision and represent its more operational side.

Among the key elements are:

- a commitment to triple adaptation finance by 2035, with an explicit call on developed countries to increase support for the most vulnerable;

- the conclusion of the Baku Adaptation Roadmap, which sets out a programme of work through to 2028, in view of the next Global Stocktake, with clearer milestones and responsibilities;

- the definition of 59 voluntary indicators to measure progress towards the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), with a focus on water, agriculture, health systems, infrastructure and ecosystems, as well as finance, technology and capacity-building.

The Parties also approved a just transition mechanism that explicitly puts people and equity at the centre: the transition cannot be limited to swapping technologies, but must accompany workers, local communities, women and Indigenous Peoples, strengthening cooperation, technical assistance and knowledge-sharing. Alongside this sits a strengthened Gender Action Plan, which recognises the role of women – in particular Indigenous, Afro-descendant and rural women – as protagonists of climate policy, not only as vulnerable groups.

Finally, the Mutirão Decision launches two new voluntary tools for the phase now opening, that of implementation:

- the Global Implementation Accelerator, to support countries in the concrete delivery of their NDCs and national adaptation plans;

- the Belém Mission to 1.5, an action-oriented platform aimed at keeping the 1.5°C trajectory alive through greater ambition, cooperation and investment.

These decisions are imperfect and fall short of the scale of the climate emergency. But they do indicate that multilateralism, for all its limits, is still alive – and that a significant part of the world continues to move forward even when the United States is less central in the negotiations.

Colombia, the Fossil Fuel Treaty and the Belém Declaration: signals “from below”

If we look only at the official COP30 text, fossil fuels are conspicuous by their absence. And yet, outside the Mutirão Decision, important steps were taken in Belém precisely on this front.

COP30 was, in many respects, a coming-of-age COP for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, the initiative calling for a global treaty to halt the expansion of fossil fuels, manage their orderly phase-out and ensure a just transition. The leading player in this advance was Colombia.

On 21 November, in the COP pavilions, the governments of Colombia and the Netherlands announced the first international conference on the phase-out of fossil fuels. Colombia’s Minister of Environment Irene Vélez Torres and the Dutch Vice-Prime Minister and Minister for Climate Policy Sophie Hermans announced that this historic meeting will take place on 28–29 April 2026 in Santa Marta, Colombia. The choice of venue is far from random: Santa Marta is a key port for coal exports in a country that is the world’s fifth-largest coal exporter. It is a powerful message: the debate on how to close the fossil fuel era starts in a territory that still depends heavily on them.

In parallel, the Belém Declaration on a Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels was launched, supported by 24 countries, including nine European ones such as Spain, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Finland and Luxembourg. Italy, for the moment, is not among the signatories. In the texts and speeches of the promoters, a strong idea keeps returning: a “moral responsibility” to give voice to the demand for climate justice and fossil fuel phase-out – a transition that is necessary not only for the climate, but also for the resilience of economies and collective security.

In other words, while the official negotiations stop just short of naming fossil fuels explicitly, a growing coalition of countries, led by the Global South, is organising to build the “after”. The Santa Marta conference in 2026 will sit alongside existing UN processes and delve into the legal, economic and social conditions for an orderly phase-out: from impacts on trade to the removal of subsidies, from macroeconomic stability to energy security, through to labour transition and the scaling up of renewables.

Why Belém (and the Amazon) were the right place

Experiencing COP30 in Belém means seeing, in the same corridor, government delegates, Indigenous leaders, representatives of major companies, youth activists and civil-society organisations.

The city, with its contrasts, made three aspects especially tangible. First: climate is not a purely “technical” issue, but a deeply social and political one. It is about international trade, jobs, industrial policy, food security. If we want to help write the rules of the future, we need to be present at these tables, not just comment on them from afar.

Second, historically marginalised voices are increasingly central – above all those of Amazonian Indigenous Peoples, who brought a clear message to this COP: without protection of territories, there is neither forest nor climate stability.

The third aspect concerns the rest of the world, which is advancing on climate even without US leadership. This emerged particularly clearly in relation to climate finance and the new alliances between Global South countries and Europe. It is a geopolitical signal that is reshaping both power balances and opportunities.

Where business is heading (and why there is reason for optimism)

During my days at COP30, I followed several events devoted to the role of business in the climate transition. It became very clear that these actors are driving markets and have enormous power in determining how – and how quickly – the green transition will take place.

As Rana Ghoneim, Director of the Energy and Climate Action Division at UNIDO, put it: “If green represents the choice of the global market, then green is the future.”

Coming from Europe, where some of the obligations linked to the CSRD are being softened by the Omnibus Package and many companies perceive a weakening of the “ESG compass”, COP30 gave me renewed optimism: it confirmed that the world has already taken the sustainability path. Companies are innovating and, to remain competitive, sustainability is no longer optional – it is essential.

Corporate strategies: innovation, value creation, efficiency

This awareness was reinforced by the intervention of Alex Carreteiro, Director of PepsiCo Alimentos Brazil, who stressed how growth, market share, people and sustainability now go hand in hand. He described projects on regenerative agriculture and the use of biomethane which generate very tangible win–wins: lower operating costs, environmental regeneration and added value along the entire value chain.

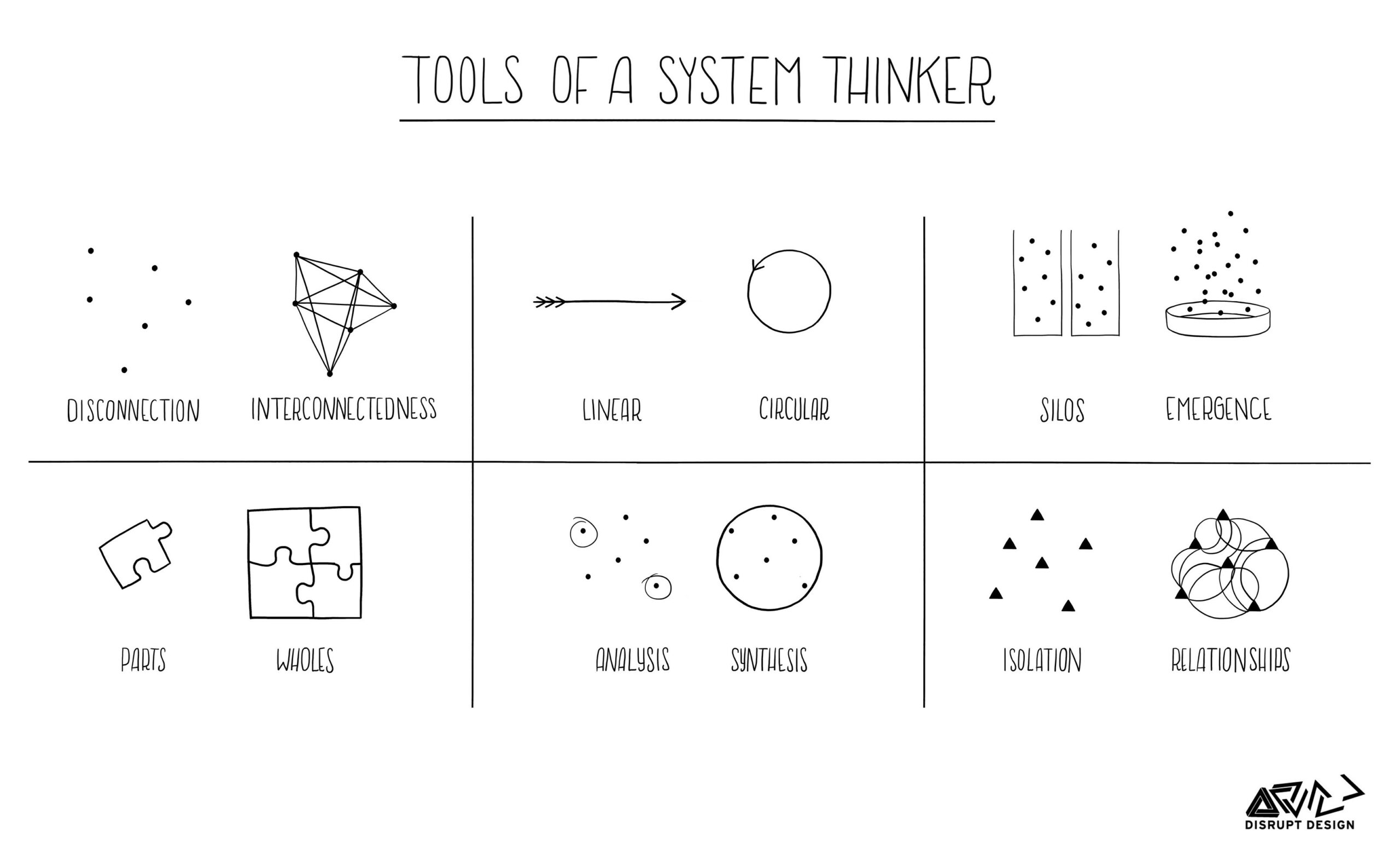

In another panel, a representative from Schneider Electric explained how the company has built its supply-chain strategy using all the SDGs as its overarching framework. This approach has improved performance across all ESG dimensions while at the same time generating profit and operational efficiency.

Accountability and governance as the foundations of credibility

Accountability was a recurring theme. In this context, reporting is increasingly seen as the backbone of corporate credibility.

The report presented at COP by the PRI Net Zero Taskforce, Policy Matters: From Pledges to Delivery a Decade after Paris, highlights how accountability mechanisms are the “connective tissue” between ambition and delivery. The Taskforce’s work shows that:

- there is a growing shift towards mandatory, standardised climate-disclosure systems;

- there has been strong progress on emission-calculation requirements;

- rules on transparency in risk assessment and on the integrity of transition plans are advancing more slowly.

At the same time, governance is becoming the bridge between commitments and action: there is greater focus on top-management responsibility, the role of boards of directors and remuneration systems linked to climate objectives. Climate litigation is emerging as a catalyst for political and regulatory action, pushing companies to prepare for increasingly concrete regulatory and legal risks.

The perspective of finance: disclosure as the gateway to capital

Helena Viñes Fiestas, Commissioner at the Spanish CNMV and Chair of the EU Platform on Sustainable Finance, stressed the importance of clear reporting. She recalled that ESG investments now account for a majority share of the European financial market, and that disclosure is the gateway to capital.

She highlighted three crucial aspects:

- Prioritising double materiality, with particular attention to financial materiality, especially in relation to the risks of stranded assets.

- Distinguishing information that is truly useful for the transition from redundant data: ideally, the sustainability report should be increasingly integrated with the financial statements.

- Taking market dynamics into account, recognising that sustainability is now embedded in the way assets are valued and depreciated – and therefore in the overall valuation of a company.

Public policy and the new leadership of emerging economies

In a context of growing ambition in the private sector, public decision-makers are trying to keep pace by defining emission-management measures and common measurement systems. As highlighted in the presentation of the World Economic Forum’s report Making the Green Transition Work for the People and the Economy, private-sector ambitions need to be aligned with the opportunities created by the public sector.

Rana Ghoneim emphasised that it is increasingly emerging economies that are leading the transition, more than Europe and the United States. Brazil is one such example: through its COP presidency and the Belém Declaration on Sustainable Public Procurement, it has set out an ambitious plan to use public procurement as a lever to align high-impact markets and value chains with the 2030 Agenda.

A clear global direction, despite European uncertainty

COP30 confirmed that, despite regulatory hesitation in Europe and the United States, the global trajectory is now clearly set: businesses, governments and international institutions are moving towards an economic model in which sustainability, competitiveness and innovation are inseparable.

Companies are accelerating, policy-makers are defining enabling frameworks, and the data increasingly show that alignment with the transition is a driver of economic value. At the same time, emerging economies are assuming leadership roles, demonstrating that sustainability can be a lever for development, not a constraint.

For European companies, this means that the question is no longer whether to invest in the transition, but how, and how quickly: in terms of governance, skills, product innovation, supply-chain relationships and access to capital.

At the end of the conference, after her intervention, I asked Helena Viñes Fiestas directly what she expected from the future of sustainability. Her answer was, perhaps, the most valuable message I brought home from Belém:

“Hold on. The coming years will be challenging. But sustainability will return with even greater strength.”

It was not a slogan aimed at the audience, but a personal reflection shared on the margins of the panel. An invitation to strategic patience: the coming years will be complex, but those who choose to align with the transition today are not only making an ethical choice. They are choosing to remain competitive and relevant in tomorrow’s global market.

Sources

Mutirao Decision

https://dwtyzx6upklss.cloudfront.net/Uploads/u/r/l/2025_tnzp_cop30_report_605206.pdf

https://www.weforum.org/publications/making-the-green-transition-work-for-people-and-the-economy/ https://netzeroclimate.org/new-plan-aims-to-make-public-procurement-a-force-for-climate-action/

Author

Annika Zamboni

With a background in economics and languages, Annika earned her degree in economics and subsequently completed a double master’s in management and sustainability at the universities of Trento and Bremen. After gaining experience in the banking sector and in tax and sustainability consulting, Annika now supports companies, including SMEs, at Terra in the development of business strategies and reporting. She also deals with the EU taxonomy.

Questions? a.zamboni@terra-institute.eu or make a brief appointment.